Date : Jun 25 , 2020 | Opinion

Akanksha Agarwal of India Education Collective says the lockdown poses important questions about how we approach education and understand learning; we have an opportunity now to pause and find answers to these questions.

Summer always brings back childhood memories of long school breaks and anticipation of what the next year at school would be like. Yet, this summer, most children are simply longing to go back to school – and we have no idea when that will actually happen.

With schools shut for almost three months, children have been suddenly forced to adapt to new ways of learning. Some of them have been accessing learning through phones and laptops. Several private schools have shifted to online classes. My niece in Grade 3 now knows more about Zoom and Microsoft Teams than me; she and her classmates have also figured out how to privately message each other without getting caught by the teacher!

Despite the classroom going online, one thing hasn’t changed: the teacher is still the one speaking and most children—now outside the four walls of the classroom—are still zoning out. If they were doodling and daydreaming in the classroom, they are doing that sitting in front of computers. Some are also finding it difficult to adapt to the new normal. I heard my five-year-old nephew, whose kindergarten classes are now on Zoom, tell his mother that school isn’t for him as listening to his teacher gave him a splitting headache. My niece, on the other hand, wants to go back to school because she misses her friends. The daily interaction and engagement with other children, the foundation of all learning, has taken the biggest hit in the current context.

Besides their online schooling, my niece and nephew are doing a lot more on their own. They have designed their own games using discarded and old stationery items. Their boredom is giving them the freedom to experiment and explore. Observing that they are learning a lot more from each other has reaffirmed my belief that learning can happen anywhere, anytime and through anyone.

The sad part, though, is how our society still perceives learning. Many well-intentioned parents, for instance, feel that children are not learning enough during their online classes. They are therefore adding to the burden on their children by having them attend tuition classes on Zoom so that they can ‘revise’—basically try to recall, repeat and memorise—what was taught at (online) school earlier.

[Also read: ‘The spirit remains the same, the ambition is bigger’, with Safeena Husain from Educate Girls]

Our collective obsession with revision, recall and memorising is deep. As a result, this crisis innovation of online schools has ended up becoming a continuation of the old offline classroom. We have transferred all the flaws of the physical classroom to the online space.

We forget that learning can only be facilitated. And both the classroom and online meeting rooms are mediums through which students can either be instructed or provided with opportunities to explore, question, share and understand.

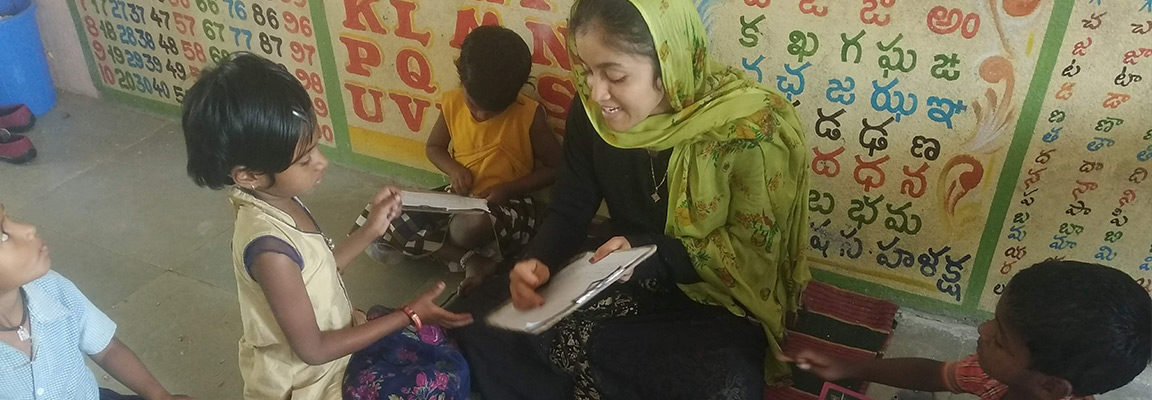

Teachers are struggling equally in this transition. They need support and spaces where they can discuss their issues and concerns, especially in the new context where the challenge is more in terms of engaging with children in a medium that is unfamiliar. At the India Education Collective, our approach towards teacher empowerment has been to facilitate monthly teacher meetings at the cluster level, wherein teachers collaboratively solve their challenges. It is difficult to replicate the engagement and interaction using current technology tools. The importance of peer learning and support amongst teachers is and will remain an important process for any effective education system. How are we thinking of addressing these kinds of requirements?

For those of us who earnestly desire a transformation in education, the question remains: How do we create meaningful learning opportunities for all children whether through online or offline platforms? Moreover, how do we serve children who have no access to online platforms? Only one-fourth of our children reportedly have access to online learning tools. What is happening to their learning when schools remain shut?

Whilst we have faith that their imagination would have helped them find resources within their environment to continue their journey of exploration, we also know that isn’t enough. Besides nutrition through the mid-day meal, the regular interaction and engagement for learning in the schooling environment is equally important.

We need to be prepared for multiple scenarios. Students may return to the classroom with limited ability to ‘bring back’ what they had memorised before schools shut. Instead, they will carry new knowledge into the classroom: children do not waste time; they observe, engage, play and imagine. And when they come back to schools, they will bring all of this with them. Are we willing to broaden our notion of learning to include these fundamental abilities of observation, asking questions, interpretation and more?

Many schools reluctantly cancelled end-of-year examinations in the last academic year because of the pandemic and lockdown. The reluctance came from the over-dependence on exams being the singular source of information to know how much the student has learnt (or, the ability to recall). On the other hand, if the entire year had held evidence of learning through different mechanisms that documented ‘learning with understanding’ and ‘learning by doing’, the system could have handled the ‘evidence’ part of learning with ease and conviction to transition the students to the next grade. Even though moving the students to the next class was an important step towards freeing both children and teachers from the dreaded exams, it did not quite change the system. Will the online medium point us to a new lesson to be learnt as schools think of restructuring their scarce time in 2020?

The reverse migration that we have been witnessing in recent months will bring more children to rural government schools, which are already under-staffed and under-resourced. Student enrolment will increase. The fears caused by this communicable disease will also increase among students and teachers. With a whole new set of dynamics at play, schools in general and rural government schools, in particular, will need a lot of our attention if we are serious about rebuilding our education system.

We have been given a moment to pause and reflect on how we have approached and understood learning as a society. The new context is challenging us to reimagine our education system; it is presenting us with an opportunity to observe how children learn, think, explore and question. Will we make the most of this opportunity?

Date : Jul 4 , 2024

Date : Jun 27 , 2024

Date : Jun 15 , 2024

Date : Apr 5 , 2024

Date : Mar 28 , 2024

Date : Jan 25 , 2024

Date : Mar 22 , 2023

Date : Mar 15 , 2022